Real or perceived barriers to healthy eating, such as having a busy job, can make it difficult for adults to devote time and financial resources to create and maintain healthy eating patterns. A 2017 cross-sectional observational study of 5,900 urban-dwelling European adults found that a busy lifestyle was reported as a barrier to maintaining a healthy diet in 42.9% of participants and irregular working hours was reported as a barrier in 31.5% of participants.1 A 1998 analysis of a Spanish national sample (n=1,009) found that 54% of surveyed adults reported time-related barriers to eating a healthy diet including irregular work hours, having a busy lifestyle, and healthy food taking too long to prepare.2

In 2012 cross-sectional analysis of the Eating and Activity in Teens and Young Adults cohort study, which included 2,287 young adults diverse in ethnicity and race, found that healthy dietary behaviors were tied to workload.3 On a self-reported survey, 33.5% of participants believed that eating healthy meals took too much time, 35.1% believed that they were too busy to eat healthy foods, 51.5% reported being too rushed in the morning to eat a healthy breakfast, 54.9% reported they tended to eat on the run, 72.0% ate fast food ≥1 time per week, and 30.3% ate ≥5 servings of fruits or vegetables per day. Higher workload was associated with poor healthy eating habits, with 43.6% of those working >40 hours per week reporting that they were too busy to eat healthy compared to 29.9% of those working 1-19 hours per week.

Another 2012 cross-sectional study of a diverse sample of community college and public university students (n=1,201) found that courseload was associated with healthy diet.4 On a self-reported survey, 44.9% of students reported that if they were less busy, they would be able to eat a healthier diet, and 23.2% weren’t confident they could find time in their daily schedule to prepare healthy meals. Among those reporting that their time constraints affected their diet, 84.4% were full time students (≥12 credits).

The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) 2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommends consuming a variety of nutrient-dense foods and beverages that can be adapted to an individual’s schedule, budget, culture, and preferences.5 They define nutrient-dense foods as those that provide vitamins, minerals, and other health-promoting components and have little to no added sugars, sodium, and saturated fat, such as vegetables, fruits, whole grains, seafood, eggs, beans, peas, lentils, unsalted nuts and seeds, lean meats, lean poultry, and low-fat dairy products. Caloric intake and daily quantity consumed of each food group are dependent on a person’s age, sex, level of physical activity, body composition, and presence of chronic disease.

The USDA recommends the following strategies to support healthy eating patterns in adults with barriers to making healthy food choices:5

- Restaurant and ready-to-eat meals are great for convenience, but one should be mindful of portion sizes and added calories in these foods. Ask for ingredients or calorie counts when available. Try to choose nutrient-dense options that are lower in calories.

- If choosing foods prepared outside of the home for convenience, choose options with the least amount of added sodium, sugar, and saturated fat.

- Prepare meals at home. Cooking at home allows for greater control over the types of food ingredients used, leading to more nutrient-dense options with less sodium, sugar, and saturated fat.

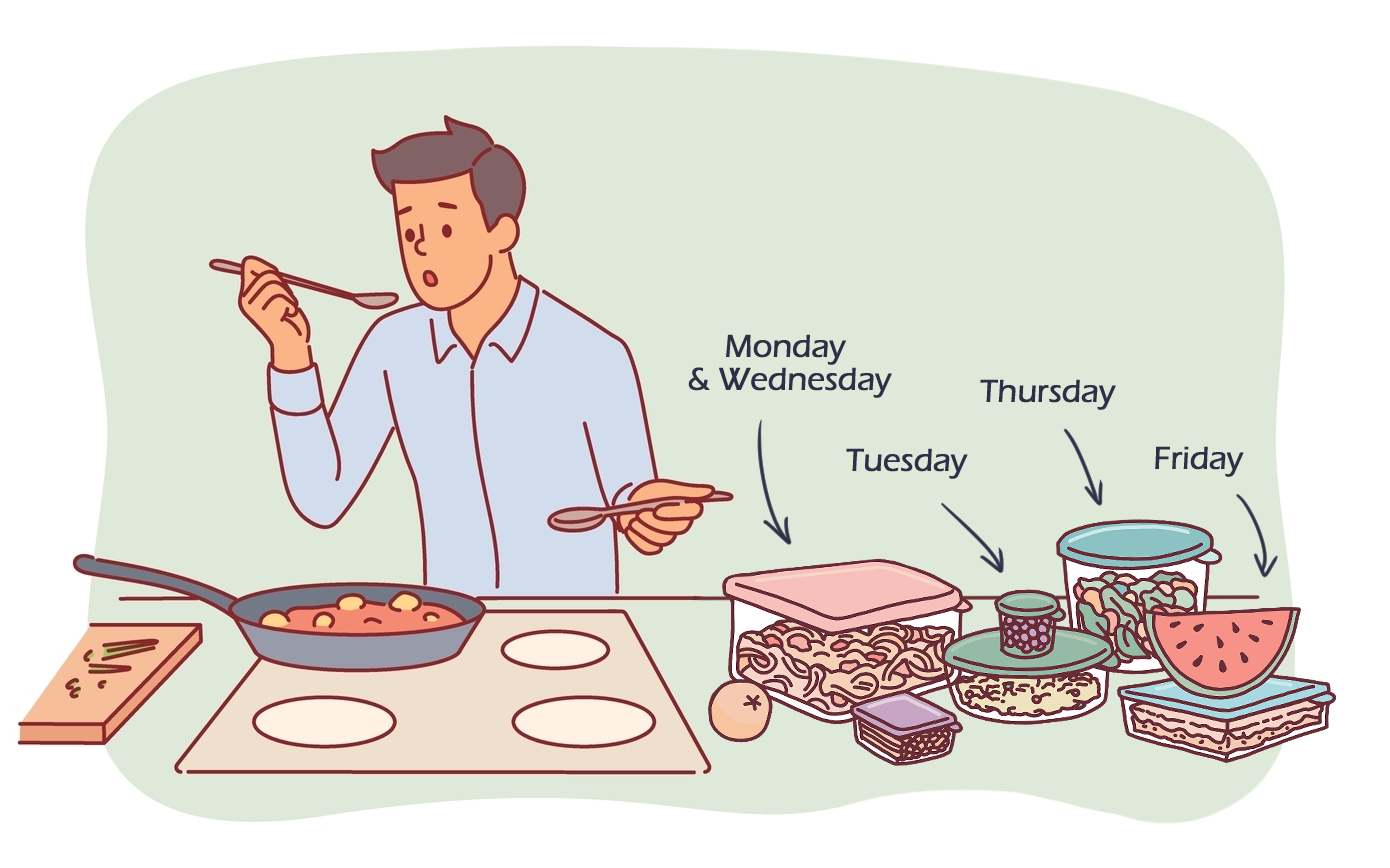

- If preparing and consuming meals at home seems too effortful or unrealistic due to time constraints, try learning a new skill or habit like meal planning. Taking time once a week to plan nutrient-dense meals and snacks ahead of time can ensure a person meets their dietary goals with little effort on the other days of the week.

- Prepare and consume meals with family and friends to foster connection and enjoyment around food. Cooking and eating together also teaches others cooking skills and models healthy eating behaviors.

- If financial constraints limit one’s ability to access healthy food, consider applying to government programs, like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) or the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC).

- If already enrolled in a program like SNAP or WIC, try joining a partner educational program such as SNAP Education (SNAP-Ed) or the Expanded Food and Nutrition Education Program (EFNEP) to learn how to eat healthy with limited resources.

- Look for local initiatives to support healthy eating in the community, such as food banks, farmers markets, community gardens, or community meal sites.

- Check if an employer has healthy meals, snacks, and beverages in workplace cafeterias or vending machines. See if they have any educational programs on healthy eating tailored to working adults.

References:

- Pinho MGM, Mackenbach JD, Charreire H, et al. Exploring the relationship between perceived barriers to healthy eating and dietary behaviours in European adults. Eur J Nutr. Aug 2018;57(5):1761-1770. doi:10.1007/s00394-017-1458-3

- López-Azpiazu I, Martínez-González MA, Kearney J, Gibney M, Martínez JA. Perceived barriers of, and benefits to, healthy eating reported by a Spanish national sample. Public Health Nutr. Jun 1999;2(2):209-15. doi:10.1017/s1368980099000269

- Escoto KH, Laska MN, Larson N, Neumark-Sztainer D, Hannan PJ. Work hours and perceived time barriers to healthful eating among young adults. Am J Health Behav. Nov 2012;36(6):786-96. doi:10.5993/ajhb.36.6.6

- Pelletier JE, Laska MN. Balancing healthy meals and busy lives: associations between work, school, and family responsibilities and perceived time constraints among young adults. J Nutr Educ Behav. Nov-Dec 2012;44(6):481-9. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2012.04.001

- Phillips JA. Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025. Workplace Health Saf. Aug 2021;69(8):395. doi:10.1177/21650799211026980