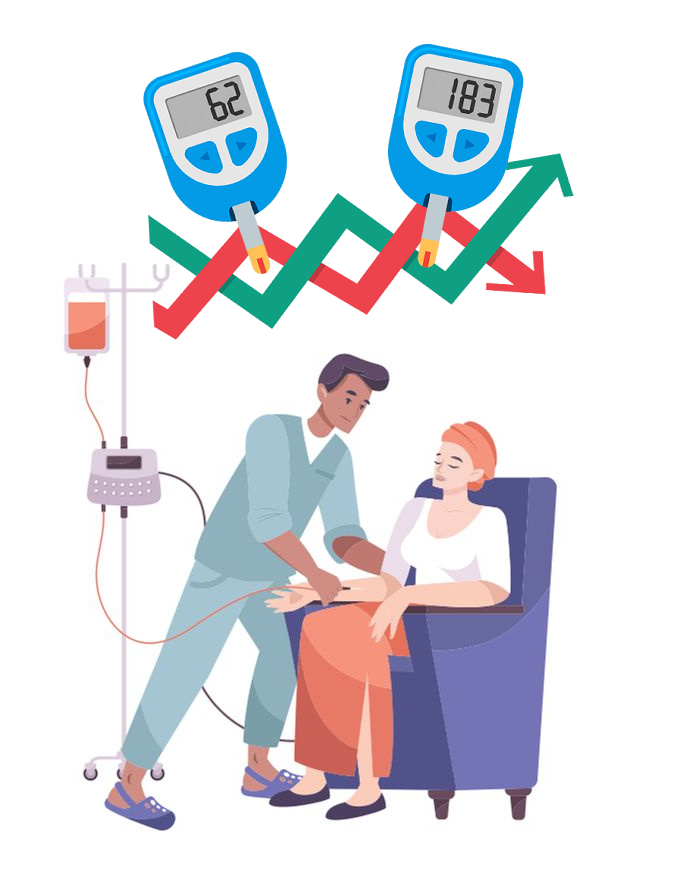

There is a well-documented relationship between chemotherapy and unexpected fluctuations in blood sugar levels in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).1,2 Chemotherapy targets rapidly growing cells including cancer cells, but also normal mucosal cells lining the mouth and intestines. As a result, chemotherapy may lead to several side effects including changes in taste and smell, nausea, and vomiting, which can lead to loss of appetite and poor intake. One study of 151 patients from community oncology clinics reported a 36% prevalence of acute chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) while 59% of patients developed delayed CINV during cycle 1 of chemotherapy.2 Some chemotherapeutic agents can also cause oral mucositis, which can be extremely painful and makes it very difficult to eat. Oral mucositis may result in dose modification to enhance tolerability.

The nausea, vomiting, and anosmia common with chemotherapy is particularly dangerous for patients with T2DM. Patients are typically instructed to continue their diabetes medication regimen, which may result in severe hypoglycemia due to reduced food intake when diabetes medications are taken at full doses. Nausea and vomiting during treatment are often managed with agents such as 5-hydroxytryptamine type 3 receptor antagonists, neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists, and dexamethasone.3 These approaches are not uniformly effective, thus nausea may continue to be a problem. Furthermore, dexamethasone and other steroids can raise blood sugar levels resulting in hyperglycemia.4 For example, when prednisone was included as part of adjuvant therapy for the Chemotherapy of Breast Cancer A Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) trial, 7.9% of the 1,237 patients enrolled had hyperglycemia following treatment.5

Several chemotherapeutic agents can cause hyperglycemia. For example, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors are associated with a high incidence of hyperglycemia, ranging from 13% to 50%; whereas immunotherapy, such as anti-programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) antibody treatment, induces hyperglycemia with a prevalence of 0.1%.6 A systematic review of 22 studies found that chemotherapy agents such as docetaxel, everolimus, and temsirolimus alone or in combination with other agents can promote hyperglycemia in up to 82% of patients.7 One retrospective study looking at androgen-deprivation therapy commonly used in prostate cancer reported that among 77 patients with pre-existing diabetes, there was a >10% increase in serum HbA1c in 15 (20%) patients and fasting glucose levels in 22 (29%) patients, respectively.8

Glucose levels can affect how much and when cancer treatments are given and, in some cases, may lead to delay or stopping of chemotherapy, reducing the effectiveness of treatment.9 When patients are hospitalized, cancer treatments may have to be delayed or stopped entirely. For patients with diabetes, poor glycemic control can increase the risk for hospitalization, increasing the chances of disrupting cancer treatment. One study of adults with T2DM taking oral antihyperglycemic agents (n=900) examined the effect of nonadherence on hospitalization. When comparing the rate at which patients filled prescriptions to the rate of hospitalization in the following year, the results were: 100% fill rate had 4.1% hospitalization, 99-80% fill rate had 10.3% hospitalization, 79-60% had 11.9%, and 59-40% had 14.8%. For just up to a 20% drop in prescription fill rate, patients’ incidence of hospitalization increased by 2.5 times (odds ratio 2.53; 95% CI [1.38–4.64]), demonstrating a strong relationship between glycemic control and risk of hospitalization.

Interruption of cancer treatment can increase risk of mortality, cancer recurrence, and lower quality of life due to severe symptoms.10 Oncologists may reduce the chemotherapy dose given to patients with T2DM in an attempt to avoid adverse hospitalizations and outcomes that can result from the chemotherapy’s effect on blood sugar. However, if less than 85% of a planned chemotherapy dose is given, cancer prognosis for patients declines.11 According to one retrospective study examining the role of dose level in postoperative chemotherapy for breast cancer, there was a clear dose-response effect indicating that the chemotherapy was useful only when given in full or nearly full dose. Those given a dose ≥85% of the planned dose had a five-year relapse-free survival of 77% as compared with 48% in patients who received <65% of the planned dose (p=0.0001).

A study investigating the relationship between biologically determined glycemic control and breast cancer prognosis found that chronic hyperglycemia was associated with reduced survival in survivors of early-stage breast cancer.12 For women with HbA1c levels ≥7.0%, there was 20.8% chance of a breast cancer-related event compared to 16.5% for women with HbA1c ≤6.5%), which is an increase of 4.3% for absolute risk. These events included: new primary tumors, locoregional recurrence, or distant recurrence. Additionally, women with HbA1c ≥7.0% had a 26% higher rate of recurrence of breast cancer-related events compared with women who had better glycemic control (HbA1c ≤6.5%). Therefore, it is important to continue monitoring glucose levels and insulin regimens should be adjusted as needed to compensate for changes such as hyperglycemia and increased insulin resistance from corticosteroids, stress, and decreased activity.13 Similarly, experts advise patients with cancer and diabetes to continue seeing the doctor who manages their diabetes to monitor and manage blood sugar during chemotherapy.

Additionally, poor glycemic control is linked with increased risk of developing infections.14 One study sought to examine the relationship between A1C levels and hospitalization for infection in 85,312 patients with T2DM. Using primary care, hospital, and mortality records, the following incidence across 18 infection categories was present for each level of glycemic control: A1C of 0-<6%=45.2% incidence of infection, ≥6-<7=43.1%, ≥7-<8=41.6%, ≥8-<9=45.8%, ≥9-<10=51.4%, ≥10-<11=51.6%, ≥11=66.7%. Those with the poorest levels of glycemic control had just over 20% increased incidence of infection compared to those with ideal A1C levels. This increased risk of infection can further put at risk a patient with T2DM who seeks surgical options to treat their cancer.

References

- (2020, September 10). Nausea and vomiting caused by cancer treatment. American Cancer Society. https://www.cancer.org/treatment/treatments-and-side-effects/physical-side-effects/nausea-and-vomiting/caused-by-treatment.html

- Cohen L, de Moor CA, Eisenberg P, Ming EE, Hu H. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: incidence and impact on patient quality of life at community oncology settings. Support Care Cancer. May 2007;15(5):497-503. doi: 10.1007/s00520-006-0173-z

- Navari RM. Managing Nausea and Vomiting in Patients With Cancer: What Works. Oncology. Mar 2018;15;32(3):121-5,131,136.

- Perez A, Jansen-Chaparro S, Saigi I, Bernal-Lopez MR, Miñambres I, Gomez-Huelgas R. Glucocorticoid-induced hyperglycemia. J Diabetes. Jan 2014;6(1):9-20. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12090

- Ellis ME, Weiss RB, Korzun AH, Rice MA, Norton L, Perloff M, Lesnick GJ, Wood WC. Hyperglycemic Complications Associated with Adjuvant Chemotherapy of Breast Cancer A Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB) Study. American Journal of Clinical Oncology: Dec 1986; 9(6):533-536.

- Hwangbo Y, Lee EK. Acute Hyperglycemia Associated with Anti-Cancer Medication. Endocrinol Metab. Mar 2017;32(1):23-29. doi: 10.3803/EnM.2017.32.1.23.

- Hershey DS, Bryant AL, Olausson J, Davis ED, Brady VJ, Hammer M. Hyperglycemic-inducing neoadjuvant agents used in treatment of solid tumors: a review of the literature. Oncol Nurs Forum. Nov 2014;41(6):E343-54.

- Derweesh IH, Diblasio CJ, Kincade MC, Malcolm JB, Lamar KD, Patterson AL, Kitabchi AE, Wake RW. Risk of new-onset diabetes mellitus and worsening glycaemic variables for established diabetes in men undergoing androgen-deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. BJU Int. Nov 2007;100(5):1060-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07184.x.

- Lau DT, Nau DP. Oral Antihyperglycemic Medication Nonadherence and Subsequent Hospitalization Among Individuals With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(9):2149-2153.

- Hershey DS. Importance of Glycemic Control in Cancer Patients with Diabetes: Treatment through End of Life. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. Oct-Dec 2017;4(4):313-318.

- Bonadonna G, Valagussa P. Dose-response effect of adjuvant chemotherapy in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1981;304(1):10-15.

- Erickson K, Patterson RE, Flatt SW, Natarajan L, Parker BA, Heath DD, Laughlin GA, Saquib N, Rock CL, Pierce JP. Clinically defined type 2 diabetes mellitus and prognosis in early-stage breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. Jan 2011;29(1):54-60.

- Leak A, Davis ED, Houchin LB, Mabrey M. Diabetes management and self-care education for hospitalized patients with cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. Apr 2009;13(2):205-10.

- Critchley JA. Glycemic Control and Risk of Infections Among People With Type 1 or Type 2 Diabetes in a Large Primary Care Cohort Study. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(10):2127-2135.